Feature image by Sunsations Photography, via the City of Treasure Island.

Look around a main street or suburban sprawl in Florida and you’ll see flamingos. From lawn ornaments to the Florida Lottery, the bright pink-and-black bird is an iconic emblem of the Sunshine State. But do they really live here?

The answer is yes and no. Until the early 20th century, flamingo colonies were much more common in Florida before development and hunting – largely because humans decided their feathers would look nicer in a hat than in the wild. The birds – along with myriad other species, particularly water birds – were aggressively hunted for their plumage. It was literally worth more than its weight in gold.

Today, flamingos are not unheard of in Florida, but their numbers are small and sightings rare – mostly in remote parts of the Everglades or the Keys.

But that changed dramatically after Hurricane Idalia swept up from the Yucatán peninsula and made landfall in the Big Bend area of Florida on August 30. As the slow-but-familiar process of storm recovery got underway, Floridians from Naples to Crystal River noticed new neighbors – flocks of bright pink American flamingos.

In the Tampa Bay area, there has been a flood of sightings, particularly on the barrier islands and in the flamingo-friendly habitat around Fort DeSoto at the southern-most point of Pinellas County.

How Did They Get Here?

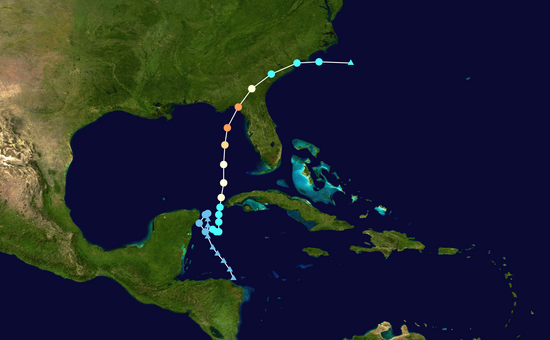

Hurricane Idalia started as a system near the Yucatán in Mexico, and, as it formed, it also passed over the western part of Cuba in the Caribbean – both known American flamingo habitats with breeding colonies. Bay area authorities have since noted that at least one of the birds had a band that originated from the Mexican flocks, and so deduced that the hurricane displaced them. The short answer, of course, is that they flew.

Hurricane Idalia formed near the Yucatan and Cuban flamingo habitats before moving up to Florida. Image via NOAA.

“The American flamingo is generally considered to be non-migratory but is a strong flier that can move large distances,” according to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC). Those big, powerful wings work even better with tropical-storm-force winds underneath them.

The good news is that the FWC considers flamingos native to Florida, so while they’re here, they have strong protections under the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act, which prohibits killing, capturing, selling, trading, and transport of the birds.

Flamingo Fever

What happens when a Florida icon is suddenly in Florida? Well, let’s just say Flamingo Fever is highly contagious! Every newspaper, local news outlet, and social media feed is awash in pink plumage, with flamingo sightings now the hottest ticket in town.

Retired attorney and St. Petersburg artist Joetta Keene originally saw a pair of the birds on North Beach in Ft. DeSoto on September 1. She then made it her mission to see them – respectfully – a little closer.

“The flamboyance is still in town, but I did not find them today. I am trying again tomorrow because I am obsessed!” she posted the next day. “The county put out a press release for everyone to give them their sightings because they rehabbed one and want to return it to the flamboyance. So, I am all in now. I read every response and have all the locations mapped out.”

Joetta’s diligence – and a few choice contacts – paid off when she got to follow a group of birder photographers out to a remote wading location where they could view the birds from a distance without disturbing them.

“Found them!” she enthused. “You gotta want it to trek through stanky muck with jellyfish and flesh-eating bacteria. The really good pictures were taken by the photographers who were laying in the muck. What a BLAST!!!!”

One of the professional shots from the photographer field trip Joetta joined. Photo by Allison Burkhard Photography.

A Peachy Rescue

Just days before the storm, the Seaside Seabird Sanctuary in Indian Shores, Florida, recruited a bevy of staff and volunteers to evacuate all their resident and injured birds to higher ground – and then bring them all back once the danger had passed. But there was soon to be a new guest.

On September 2, the sanctuary reported that they had a rescued flamingo in their care that was “in overall good condition but is quiet and clearly exhausted.”

The sanctuary consulted with other area animal experts – including Busch Gardens of Tampa Bay, home to multiple species of flamingos – to care for the leggy new patient, whom they dubbed “Peaches.”

In response to an outpouring of concern, the sanctuary posted: “Our hospital team is working on getting the flamingo back to full strength and a healthy weight for release back into the wild as soon as possible!”

On September 10, Peaches – whose gender has yet to be determined – was released and took its time getting used to the surroundings.

“While they did not give us a grand departing initial flight, we were treated to a show of rousing, bathing, preening, and even the quintessential ‘flamingo dance’ as they stirred up the sediment while foraging in the water. After about an hour, Peaches took flight!”

The sanctuary is optimistic that Peaches – who was fitted with a federal band, a resight band, and a satellite transmitter to track their movement – will reunite with other flocks in the area. According to the sanctuary, Peaches is “only the second flamingo ever to be banded in the U.S., and the transmitter will provide incredibly valuable data and insight into their movements for at least 2-3 years.”

Peaches might not love the bands, they said, but shouldn’t be inhibited by wearing them.

“The bands and transmitter weigh about as much as a pen, and while [they] may be a little annoying for the bird initially, it will not cause pain or distress to the bird. We also will know in a few weeks whether Peaches is male or female from DNA testing!”

Will They Stay?

While the Idalia flocks have been myriad and widespread – there have been sightings up and down the East coast, with flamingos reported as far north as Ohio – storm strays are not unprecedented.

In 2018, in the wake of the devastating Hurricane Michael in Florida’s Panhandle, one wild flamingo defied the odds.

“Pinky,” as it is known to locals and visiting birders, took up residence in the splendid environment of the St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge and has not left. And, according to the Tallahassee Democrat, Pinky isn’t even the first. Hurricane Allison in 1995 and Hurricane Agnes in 1972 both skirted Cuba and the Yucatán, and both brought single, stray flamingos to the area.

So, while bird experts note that those flamingos displaced in the north will doubtlessly head back to their warm, southern homes soon, there’s at least some precedent for Idalia’s strays to stay in Florida. We can only hope they feel at home here.